Introduction

The main species of chameleons commonly kept in captivity include the Veiled Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus), Panther Chameleon (Furcifer pardalis), Jackson’s Chameleon (Trioceros jacksonii), Carpet Chameleon (Furcifer lateralis), Parson’s Chameleon (Calumma parsonii parsonii), and the Oustalet’s Chameleon (Furcifer oustaleti). Chameleons are renowned for their remarkable ability to change color and possess a highly specialized piece of anatomy: their tongues. While their color-changing ability often steals the spotlight, it’s the length and agility of a chameleon’s tongue that truly sets them apart from other animals. In this article, we delve into the astonishing anatomy of a chameleon’s tongue, exploring the length, speed, and evolutionary adaptation that makes it a formidable tool for hunting and survival. By the end of this article, you’ll gain a deep understanding of why a chameleon’s tongue is so long and how it functions.

Tiny Chameleons' Tongues Pack Strongest Punch (High-Speed Footage) - National Geographic

What is the basic Anatomy of a Chameleon?

How Long is a Chameleon's Tongue?

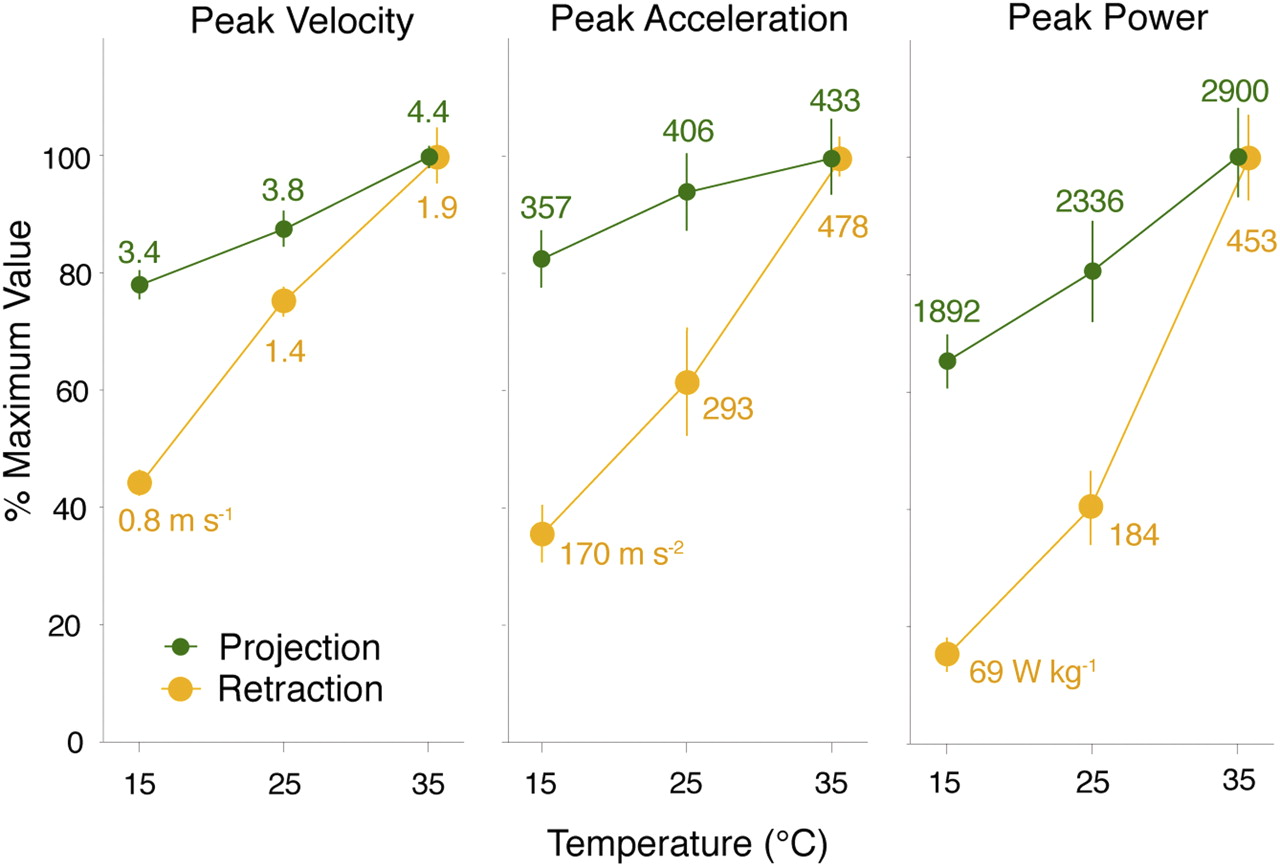

On average, a chameleon’s tongue measures approximately one to two times the length of its body, but in smaller chameleon species, this can reach up to 2.5 times their body length (measured from snout to vent). Remarkably, measurements of tongue acceleration and power in small chameleon species have set records, surpassing those of all other mammals, birds, or reptiles, including larger chameleon species (Anderson 2016). This impressive elongation is facilitated by specialized muscles and connective tissues within the chameleon’s mouth, enabling rapid extension and retraction.

| 20 Chameleon Species' Tongue Lengths Arranged by Relative Size Ratios | |||

| Data from Off like a shot: scaling of ballistic tongue projection reveals extremely high performance in small chameleons, Anderson 2016 | |||

| Species | Max SVL (in) | Max projection distance (in) | Max Tongue to SVL Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

How far can a Chameleon's Tongue Stretch?

Why Do Chameleons Have Long Tongues?

The remarkable length and agility of a chameleon’s tongue have evolved over millions of years. In their natural habitats, chameleons often dwell in dense foliage, where catching prey demands swift and precise movements. Through natural selection, individuals with longer tongues have gained an edge in the competition for food, leading to the evolution of this extraordinary feature.

Moreover, a chameleon’s tongue is remarkably versatile, capable of targeting a wide range of prey, from small insects to larger arthropods. This adaptability boosts the chameleon’s survival prospects in various ecosystems. Unlike many animals, a chameleon’s tongue is an elongated muscular structure that can extend rapidly to remarkable lengths. This rapid extension is vital for capturing prey, as chameleons primarily rely on their tongues to seize insects with exceptional precision. Compared to other predators that rely on locomotion for hunting, the muscle contraction and elastic recoil mechanism of a chameleon’s tongue is particularly effective, especially in cooler temperatures.

How do Chameleon Tongues Work?

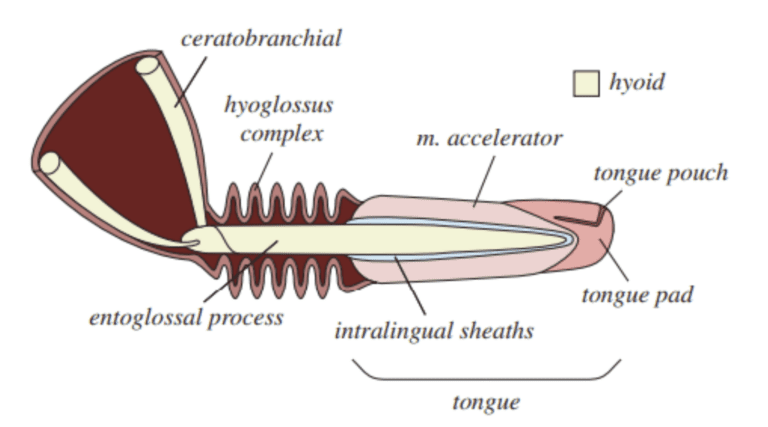

The chameleon tongue comprises three distinct elements, each with a crucial role in its projection mechanism: the entoglossal process, the accelerator muscle, and the network of intralingual sheaths. At the core of this complex lies the entoglossal process, a central bone mostly parallel-sided but tapering at the anterior-most 1-1.5% of its length. Attached to this bone are the intralingual sheaths, consisting of collagenous tissue between the accelerator muscle and the bone. Recent research (Anderson 2016) has highlighted the significance of these sheaths in storing and releasing energy during projection, shedding new light on the mechanics of chameleon tongue movement. - (Shunyuan Xiao 2023)

Chameleon tongues are extremely fast and long, usually even longer than the chameleon’s body. They can shoot out really quickly, in just a fraction of a second, to catch flies, bees or other pollinators. Here’s how it works in layman’s terms:

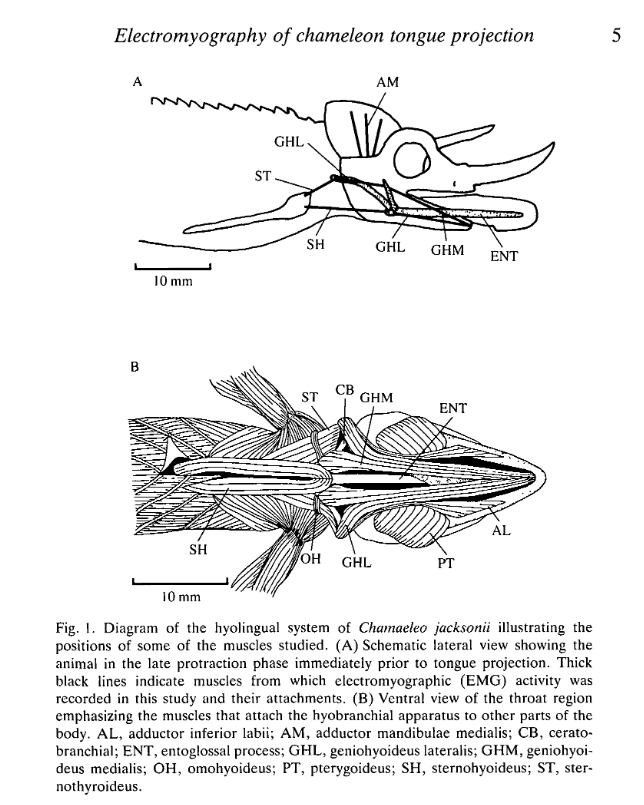

The tongue is connected to the back of the mouth by a “U” shaped bone (ceratobranchial or hyoid bone). Chameleons use the same muscles as humans do to move their tongues and swallow, but their tongues have some special features.

The tongue has a hollow part that slides over a long, thin spike called the hyoid horn (entoglossal process). This spike is connected to the middle of the “U” shaped bone. The tongue has three main parts: a sticky tip, muscles that retract it, and muscles that shoot it out (intralingual sheaths). When the chameleon is ready to catch something, it moves its tongue to the front of its mouth and lifts the hyoid bone up. Then, it aims and shoots out its tongue.

The hyoglossus complex works like rings that squeeze around the hyoid horn, pushing the tongue out really fast. The tongue is coated in saliva that helps it stick to prey. After shooting, the tongue is on its own. The chameleon can adjust how far it shoots by using tendons attached to the tip of the hyoid horn.

The tip of the tongue looks like a club and is covered in sticky saliva that helps catch prey. High-speed pictures show a flap of skin trailing behind the club, which helps wrap around prey. However, wet prey like worms or slugs can be hard to catch because the saliva won’t stick to them.

When the chameleon pulls its tongue back in, it uses special muscles that fold around the hyoid horn. These muscles stretch out to the tip of the horn when the tongue extends, and then contract to bring the tongue back in. The tongue can pull in about half of the chameleon’s body weight. While shooting the tongue out quickly is important for catching prey, pulling it back in doesn’t need to be as fast. Most of the time, the tongue collapses and recoils back in like a noodle being sucked up.

If you would like a good read from 20 years ago on this topic, check out Ken Kalisch’s article from 2003 (Kalisch 2003).

How Fast can a Chameleon's Tongue Travel?

When a chameleon spots its prey, it sets off a lightning-fast sequence of movements. First, it locks its binocular vision onto the target with remarkable accuracy while its tongue muscles contract. Then, the chameleon’s tongue is swiftly propelled forward, reaching speeds of over 12 miles per hour in just 1/100th of a second.

This rapid motion concludes with a slower retraction phase as the prey is pulled back into the chameleon’s mouth, where it’s crushed with astonishing force. Once captured, the chameleon’s tongue pouch ensures the insect remains firmly attached. This entire process unfolds in a fraction of a second, highlighting the agility and precision of chameleon prey capture mechanisms.

| 20 Chameleon Species' Tongue Projection Speeds | |||

| Data from Off like a shot: scaling of ballistic tongue projection reveals extremely high performance in small chameleons, Anderson 2016 | |||

| Species | Max projection duration (ms) | Max peak velocity (mph) | Max peak acceleration (ft s−2) |

|---|---|---|---|

How does Temperature Affect a Chameleon's Tongue Speed?

Lower temperatures affect chameleon tongue retraction speeds more than they affect projection speeds. This figure is from a study of Veiled Chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) capturing prey under various temperatures and it shows that they were able to maintain high performance in low temperatures. As we discussed earlier, this is an incredible advantage over other reptiles which need to chase down their prey after heating up.

What are some common chameleon tongue health problems?

The two most common health issues which affect tongue health in chameleons are Vitamin A deficiency and Metabolic Bone Disease (MBD). MBD can weaken or deform bones required to project their tongue and Vitamin A deficiency causes aiming problems via poor eye health.

Dehydration, illness, such as respiratory infection, and eye injury can negatively affect your chameleon’s ability to capture prey with their tongue. These are usually temporary and after you fix the issue, their tongue function should return to normal.

Another common problem we have seen is when a chameleon injures its tongue while attempting to capture stationary prey, such as hornworms. This can lead to a tug-of-war scenario, potentially causing muscle strain or tendon tears in the tongue.

Lastly, sharp DIY feeder cups can also result in tongue decapitation. Please avoid leaving freshly cut plastic edges near where their tongue will fly. And better yet, get yourself a proper feeder run cup from Sunset Chameleons or Full Throttle Feeders.

Conclusion

In summary, the length of a chameleon’s tongue is a remarkable example of nature’s ingenuity. From its lightning-fast projection to its exceptional retraction and capture abilities, the chameleon’s tongue stands as a testament to evolutionary adaptation. By delving into the mysteries of this extraordinary organ, we develop a deeper admiration for the intricate mechanisms of these incredible creatures. So, the next time you observe your chameleon, pause to marvel at the hidden wonder within its mouth - a tongue that surpasses any other reptile, bird, or mammal in power and length, relative to its body size.

Frequently Asked Questions Back

Anderson (2016) collected data on 20 different species of chameleons which we have presented a few different ways above. Here is the raw data exactly as it was presented in Prof. Anderson’s 2016 paper:

| Minimum and maximum values of Chameleon Tongue Length and Speed | ||||||||

| Data from Off like a shot: scaling of ballistic tongue projection reveals extremely high performance in small chameleons | ||||||||

| Species | Sample size | Min./max. SVL (mm) | Min./max. Jaw length (mm) | Min./max. Max. projection distance (mm) | Min./max. Min. projection duration (ms) | Min./max. Max. peak velocity (m s−1) | Min./max. Max. peak acceleration (m s−2) | Min./max. Max. peak muscle mass-specific power (W kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

References

Anderson, Christopher V. 2016. “Off Like a Shot: Scaling of Ballistic Tongue Projection Reveals Extremely High Performance in Small Chameleons.” Scientific Reports 6 (1): 18625. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18625.

Anderson, Christopher V., and Stephen M. Deban. 2010. “Ballistic Tongue Projection in Chameleons Maintains High Performance at Low Temperature.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (12): 5495–99. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910778107.

Debray, Alexis. 2011. “Manipulators Inspired by the Tongue of the Chameleon.” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics 6 (2): 026002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3182/6/2/026002.

Kalisch, Ken. 2003. “The Oddities of the Chameleon - The Tongue.” Chameleons! Online E-Zine. http://www.chameleonnews.com/03JulKalischTongue.

Shunyuan Xiao, Sophie Allard, Marc Srour. 2023. “A Biomechanical Review of Animal Tongue Functions.” Bioengineering Hyperbook.

Wainwright, Peter C., and Albert F. Bennett. 1992. “The Mechanism Of Tongue Projection In Chameleons: I. Electromyographic Tests Of Functional Hypotheses.” Journal of Experimental Biology 168 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.168.1.1.