| October 14, 2022

The best Panther Chameleon breeders have a deep understanding of their genetics, inheritance patterns and can help you get what you want. This knowledge plays into the ethics of selling Panther Chameleons because there is a lot of false advertising in the industry which is very surface-level without much understanding of the species. This is our answer to the filtered images and click-bait on Instagram and TikTok. Our Panther Chameleons for sale are high-quality, well-researched animals.

Introduction

Given that Panther Chameleon (Furcifer pardalis) colors are polygenic traits, and Panther Chameleons are a sexually dimorphic species, selective breeding for a given color is challenging and many breeders fail to achieve a consistent result. If you are not familiar with what a polygenic trait is, you should probably start by reading our previous post about our Furcifer pardalis Body Color Inheritance Theory. Polygenic traits do not have discrete outcomes, and they produce a distribution of results. The distribution’s mean is roughly situated between the sire (father) and dam (mother). However, when breeding for male color, the dam’s traits are completely unknown due to their sexual dimorphism. Initially, dam’s traits can be estimated using their male ancestors. After having a few clutches, we can use a dam’s male offspring to understand their trait distribution better. For sires, we can just look at them, so there is less uncertainty there and their ancestry is less important for selective breeding purposes (although not completely irrelevant).

Animals that transition from one phenotype to another are very common. I call those animals “rainbows” because they never actually fit in only one phenotype. They are a mix of phenotypes. At certain times, one phenotype seems to dominate, but the mix is always there. We currently breed for two Ambilobe phenotypes: yellow body blue bar (YBBB) and red body blue bar (RBBB). Our goal is to achieve a clean phenotype without rainbow tendencies - shifting or mixes of colors.

Most breeders do not understand Panther Chameleon genetics and will not be able to produce a clean YBBB or RBBB consistently. Many will even throw their hands up and say “you can’t know.” Consistent results are hard because of polygenic traits, sexual dimorphism, retained sperm, unproven females, rainbow males, incomplete lineage, inaccurate estimates for pairings/females/traits and the need for genetic diversity. We learn more about Panther Chameleon genetics with each pairing and share our results in blog posts and photo galleries. Hopefully, that provides a better grounding for what we know, and it is a valuable contribution to our hobby.

Base Estimate

When adding a new animal to our project, we start with a base estimate for what traits they carry. The first challenge with that base estimate for any pairing is being able to identify traits in male Panther Chameleons. Just like being able to see whether a Ball Python has Pastel, Yellow-Belly, or Enchi, we need to be able to observe male Panther Chameleon traits. If we don’t have an accurate base estimate for a male’s traits, nothing else matters.

Many people do not see dirty colors - if they see some yellow, somewhere, anywhere… “it is yellow!” However, we need to look for every color that is present. Red between the scales at the dermal layer can bleed up to the top layer in the offspring. Red rain mixed with yellow can become more red over time or in the next generation. Gold/orange is not neon yellow. Many people try to jam every animal into yellow-body blue-bar (YBBB), red-body blue-bar (RBBB) or yellow-body red-bar (YBRB) when very few animals actually have those extreme phenotypes, and the vast majority are in the middle. However, these extreme phenotypes are used to describe base estimates, poorly. Many people describe Ambilobe as either yellow body or red body when 95% of them are green or orange bodied, not red or yellow.

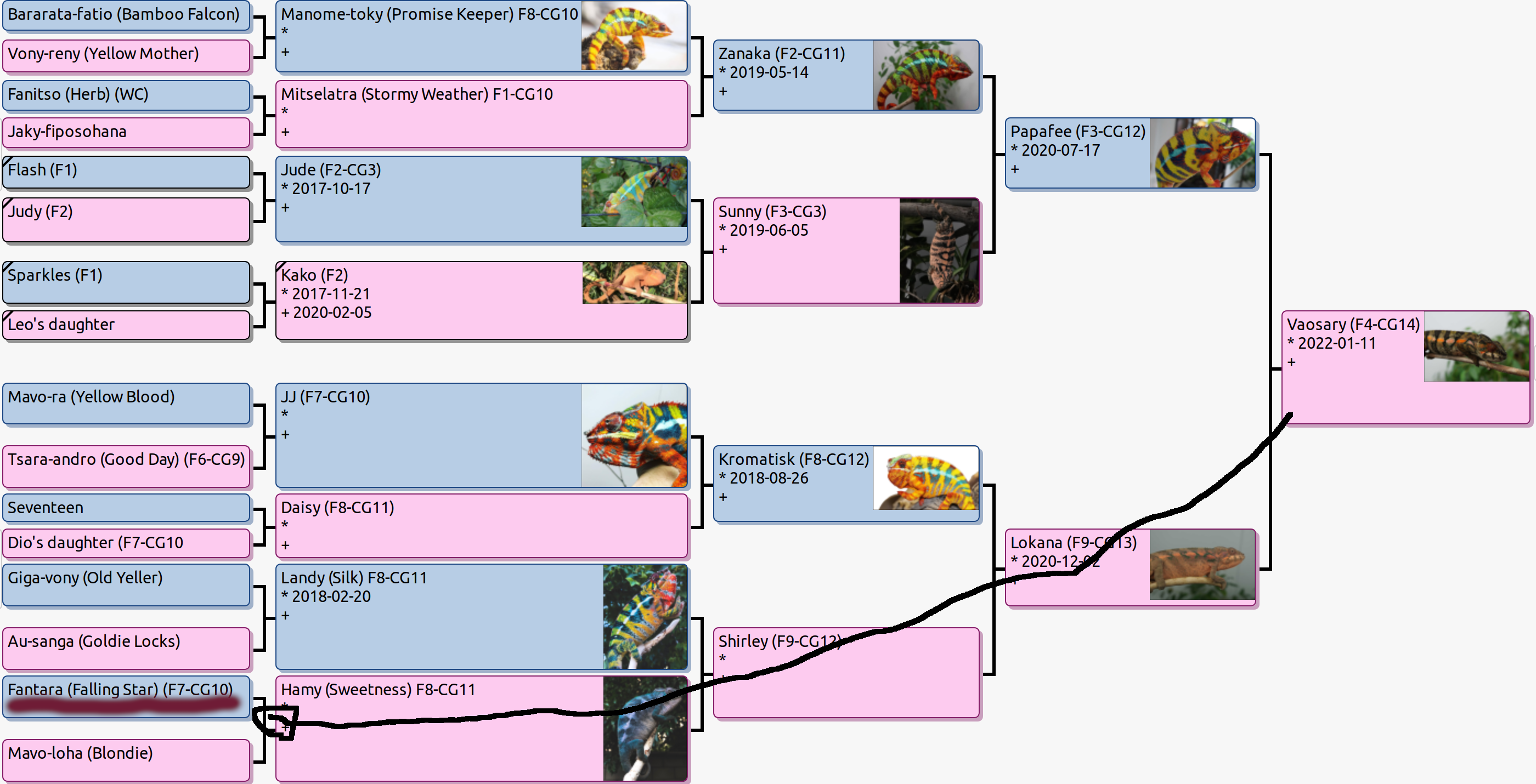

iPardalis has the goal of a base estimate of 90% or better on any animal we add to our YBBB and RBBB projects. We always publish lineage collages which represent 87.5% of the base distribution of each pairing. To do this we share the sire, dam sire, and dam’s dam sire in a collage like this:

As we work our way through a dam’s lineage, we gain information about her traits, but we can never know what she carries with 100% confidence. We look at her brothers for clues, but unless we have a large enough sample to get some sense for the mean result, we are probably just cherry picking the best brother, which is not an accurate estimate for her. That is much more likely to be a rare event than an accurate representation of the mean of the distribution, her traits. We try to ignore the outliers and focus on the average result.

| Lineage Pic | Information Gain |

|---|---|

| Sire | 50% |

| Sire’s Sire | 0% |

| Dam’s Sire | 25% |

| Dam’s Dam’s Sire | 12.5% |

| Dam’s Dam’s Dam’s Sire | 6.25% |

This table shows roughly how much information we gain from each key male relative in a lineage tree. Our lineage collages are designed to accurately represent these probabilities with the most prominent picture being the sire with other relevant sires scaled down to reflect their importance.

Notice - sire’s sire provides a 0% information gain. Every trait from the sire’s lineage is visible in him. Looking at the sire’s sire is useless information because panther chameleon colors are not mendelian traits. Traits do not skip down the sire side of a lineage tree. Sire’s sires are only helpful in determining which pairings you want to do from a genetic distance/diversity standpoint, but they are irrelevant for selective breeding purposes.

Updating Your Estimate

Before a female has been bred, her lineage is all we have to estimate her color traits. However, after her first clutch, we use her male offspring to update our original estimate and prove her out. The more male offspring she produces, the less relevant her lineage is. Somewhere around 10 male offspring is enough to get a decent estimate for her and her daughters’ traits. If her male offspring range from dark red bodies to bright yellow bodies, we can’t know what is in her daughters. It doesn’t matter if she came from yellow-bodied lineage. That result would mean that the next gen of females is completely unknown.

In our project, we do not use females from pairings which have too much variation in body color. We want to see either yellow or red bodies but not both. Any pairings where we have seen less consistency, we will drop all of the females and only use males with our desired traits. That eliminates the uncertainty and allows us to continue to produce consistent body colors, whether they be red or yellow.

This updating process is why we publish all of the male offspring from every clutch we produce, not just a few flashy hold-backs. The entire distribution and the consistent result is more important than that one-off male at the tail end of the distribution. Quality females are all about the mean of the distribution, not the 1 in 1000 result.

When we hit on a very consistent clutch like Jude x Kako, we will keep and breed as many females as we can because we know those females are going to be just as consistent as their brothers.

Proving Out Females

There are two big challenges to prove out a female:

- Raising male offspring to see their coloration

- Knowing what it is

Most first-time breeders can not do either of these things. They do not have the infrastructure to raise their males until they color up, and if they raise them in groups under sub-par conditions, their males only present stressed and submissive colors. They never get to see their true potential and genetics.

Being able to recognize early signs of rainbows vs clean phenotype outcomes in the juvenile stage of development takes practice. I often refer to young babies showing potential as “zebras” because clean colors present as white against a distinct barring that almost looks like a zebra. Then as they develop, those clean whites can fill in with a solid color. One of our best RBBB, Ralph, was an amazingly clean zebra that started to glow orange. Slowly that white filled in without any other color and we immediately stashed him around 3 months old. Small details, like a red gular, are signs of red body/rainbow results. If we are breeding for YBBB, we can see early on if the animal has red features which could become more prominent as they age.

For yellows, the green/yellow spectrum is what we want to see because there is actually a distinct chromatophore which creates color along that spectrum without the ability to produce red. There’s another chromatophore which produces color along the gold/orange/red spectrum which is often confused with yellow (it is actually gold, not neon yellow). In Ambilobe, this red spectrum chromatophore is more common at the dermal layer (between scales), so we can look for it there in juveniles. Reds often become more prominent around 6 months of age, but these animals can shift from gold to red throughout their lives. I have never seen a true neon yellow/green animal shift to red because those are actually physical differences that do not change over time.

Genetic Diversity

Sometimes we will pair a less-than-perfect male to a female we have a high degree of confidence in. We do this to add genetic diversity into the project, and we will not breed any females from these pairings unless the males prove out well. The goal is to get a nice male from the female’s lineage and avoid the less-than-perfect sire’s traits. I have sometimes pejoratively referred to these as “throw-away” clutches because the goal is to introduce genetic diversity while knowing we will not be able to use the females for fear that they resemble their sire.

The key with this process is to make sure the sire isn’t too far removed from our project goals because the chance that we will hit on a yellow body blue bar with a red body red bar sire, for example, is basically zero even if the female has yellow body blue bar lineage. The sire of a throw away can’t be too far off, otherwise, it could be a 100% throw-away clutch without any males worth keeping.

Retained Sperm

A final complication in estimating the outcome from a pairing is even knowing the sire - the most important piece of information by far (as we showed in the information gain table above). Many breeders pair multiple sires to the same dam. However, dams can retain sperm for up to 5 clutches, 18 months after the initial pairing to one sire. If she has laid 2 clutches and is then paired to different sire, she could lay 3 clutches with completely unknown lineage. Breeders will report the wrong lineage with certainty while some of those “odd ball” results are actually just coming from the first sire. Layer this onto the fact that people aren’t capable of identifying traits in their males, and we could have a very poor estimate for what will come from a given pairing.

At iPardalis, we like to see more than 50% infertility before pairing a female to another male. We also try to make sure subsequent pairings to the same female are from closely related males so a retained-sperm baby would be very close to the stated lineage. Many breeders do life-long pairings between one male and one female which is the gold standard for avoiding this problem.